- Joined

- Jan 17, 2010

- Messages

- 5,131

- Reaction score

- 6,280

Naman Karl-Thomas Habtom

Monday, August 21, 2023, 2:00 PM

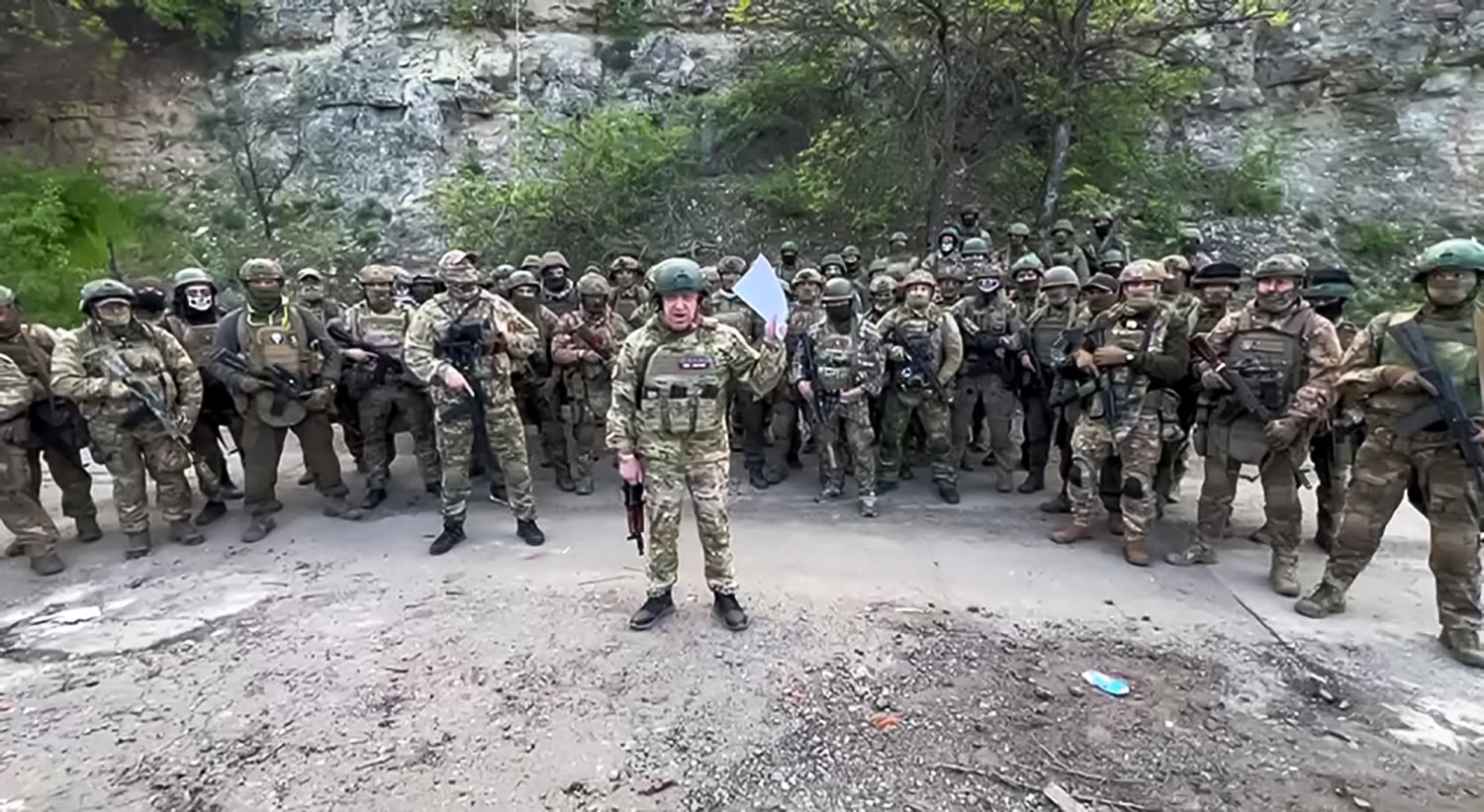

The aborted Wagner Group mutiny likely gives leaders around the world a reason to contemplate the risks of relying too heavily on PMCs.

State-owned enterprises can be found in almost every sector, from resource extraction to finance to transport. Privatization of state assets and services throughout the neoliberal era, especially following the Cold War, has spilled over to the military domain. As governments question the limits of privatization, however, private military companies (PMCs) could gradually and partially be replaced by state-owned military companies (SOMCs).

Are Private Military Companies Really Private?

PMCs, like any other industry, are heavily reliant on governmental support. One of the barriers to entry into the sector is the high cost of training personnel. Training a single recruit costs the U.S. Army anywhere from $55,000 to $74,000. This does not account for more specialized personnel, such as medics or pilots. In order to avoid this cost, PMCs tend to recruit experienced personnel, highlighting themselves as “veteran friendly.” As it stands, many security contractors benefit from a de facto military-to-PMC pipeline.

Recruitment of veterans is not limited to fellow citizens. Sometimes it is extended to foreign veterans as well. For example, Erik Prince, the notorious founder of the infamous mercenary company Blackwater, hired Colombian soldiers in a bid to train an Emirati security force. For Prince and his Emirati employers, Colombian contractors were seen as battle hardened from their time fighting Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia guerrillas (known as FARC) and are considerably cheaper than Western contractors. According to Sean McFate, a U.S. veteran turned mercenary:

When I was in the industry, I worked alongside other ex-special forces and ex-paratroopers from places like the Philippines, Colombia and Uganda. We did the same missions, but they got Third World wages. Private warriors are just like T-shirts; they are cheaper in developing countries. Call it the globalization of private force.

Regardless of where the contractors come from, their weapons are usually state sourced as well. Following years of denial, ChVK Vagner, better known as the Wagner Group, was acknowledged by Russian President Vladimir Putin as having received billions of dollars worth of funding and equipment from the Russian Federation. In the ongoing conflict in Ukraine, Wagner’s owner Yevgeny Prigozhin repeatedly requested and received materiel from the Russian Ministry of Defense. Similarly, the mercenary group’s deployments elsewhere, such as in Mali and Syria, have been largely reliant on weapons being delivered to it. While weapons could be sourced from private hands, such an approach would represent a major logistical hurdle and be far harder with non-small arms equipment, like helicopters and heavy weapons.

The biggest factor behind a PMC’s ability to fight is money. Few entities aside from national governments can afford to employ a large number of mercenaries. In the case of China, foreign veterans have reportedly been involved in training its pilots while domestic private security contractors (PSCs)—which often employ former members of the People’s Liberation Army—have supported Beijing’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative. By focusing on the developing world’s infrastructural needs, the Belt and Road Initiative has found itself in high-risk areas like Iraq and Pakistan, where Chinese nationals have been killed while working for Chinese state-owned enterprises. Meanwhile, even cash-strapped nations like the Central African Republic and Sudan are able to rely on their natural resources to fund the hiring of PMCs. Concurrently, wealthy and geopolitically energetic states like the United Arab Emirates are able to outcompete virtually any private employer in terms of pay.

Structurally, PMCs are often state trained, state equipped, and state employed. Their ownership stakes and dividend payouts are what make them private. Going forward, it is worth considering whether states will look to cut out the intermediaries who are pocketing the profits.

Monday, August 21, 2023, 2:00 PM

The aborted Wagner Group mutiny likely gives leaders around the world a reason to contemplate the risks of relying too heavily on PMCs.

State-owned enterprises can be found in almost every sector, from resource extraction to finance to transport. Privatization of state assets and services throughout the neoliberal era, especially following the Cold War, has spilled over to the military domain. As governments question the limits of privatization, however, private military companies (PMCs) could gradually and partially be replaced by state-owned military companies (SOMCs).

Are Private Military Companies Really Private?

PMCs, like any other industry, are heavily reliant on governmental support. One of the barriers to entry into the sector is the high cost of training personnel. Training a single recruit costs the U.S. Army anywhere from $55,000 to $74,000. This does not account for more specialized personnel, such as medics or pilots. In order to avoid this cost, PMCs tend to recruit experienced personnel, highlighting themselves as “veteran friendly.” As it stands, many security contractors benefit from a de facto military-to-PMC pipeline.

Recruitment of veterans is not limited to fellow citizens. Sometimes it is extended to foreign veterans as well. For example, Erik Prince, the notorious founder of the infamous mercenary company Blackwater, hired Colombian soldiers in a bid to train an Emirati security force. For Prince and his Emirati employers, Colombian contractors were seen as battle hardened from their time fighting Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia guerrillas (known as FARC) and are considerably cheaper than Western contractors. According to Sean McFate, a U.S. veteran turned mercenary:

When I was in the industry, I worked alongside other ex-special forces and ex-paratroopers from places like the Philippines, Colombia and Uganda. We did the same missions, but they got Third World wages. Private warriors are just like T-shirts; they are cheaper in developing countries. Call it the globalization of private force.

Regardless of where the contractors come from, their weapons are usually state sourced as well. Following years of denial, ChVK Vagner, better known as the Wagner Group, was acknowledged by Russian President Vladimir Putin as having received billions of dollars worth of funding and equipment from the Russian Federation. In the ongoing conflict in Ukraine, Wagner’s owner Yevgeny Prigozhin repeatedly requested and received materiel from the Russian Ministry of Defense. Similarly, the mercenary group’s deployments elsewhere, such as in Mali and Syria, have been largely reliant on weapons being delivered to it. While weapons could be sourced from private hands, such an approach would represent a major logistical hurdle and be far harder with non-small arms equipment, like helicopters and heavy weapons.

The biggest factor behind a PMC’s ability to fight is money. Few entities aside from national governments can afford to employ a large number of mercenaries. In the case of China, foreign veterans have reportedly been involved in training its pilots while domestic private security contractors (PSCs)—which often employ former members of the People’s Liberation Army—have supported Beijing’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative. By focusing on the developing world’s infrastructural needs, the Belt and Road Initiative has found itself in high-risk areas like Iraq and Pakistan, where Chinese nationals have been killed while working for Chinese state-owned enterprises. Meanwhile, even cash-strapped nations like the Central African Republic and Sudan are able to rely on their natural resources to fund the hiring of PMCs. Concurrently, wealthy and geopolitically energetic states like the United Arab Emirates are able to outcompete virtually any private employer in terms of pay.

Structurally, PMCs are often state trained, state equipped, and state employed. Their ownership stakes and dividend payouts are what make them private. Going forward, it is worth considering whether states will look to cut out the intermediaries who are pocketing the profits.